South Africa is a country with a history of state violence, structural discrimination and disempowerment. The arrival of the Covid-19 pandemic and its gradual increase in infections and deaths is more devastating for South Africa because we are still battling with inequality, poverty, crime, and gender-based violence, to name a few. Granted, the pandemic did not bring these issues, however, it brought to light what thousands of activists have lamented since the dawn of democracy. If Covid-19 does not get to you, the aforementioned ills certainly will. This is the reality of many South Africans living on the wrong side of the inequality line and below the poverty belt. Unfortunately, the focus on flattening the curve, does not mean that these issues take a pause or seize to exist. If anything, they have gotten worse, and the people who were already vulnerable, are in a worse position now more than ever.

The swift and decisive response by our political leaders and their ability to mobilize resources is highly commendable. It gives hope for a new dawn of effective leadership that we have not seen in South Africa in many years. However, this is overshadowed by the lived experiences of those living under impoverished and dangerous circumstances as well as the state’s dark cloud – corruption –ever-present and lurking for its chance to pounce on opportunity. Left unattended, these existing and exacerbated issues, coupled with corruption, could see South Africans suffering devastating effects that far exceed the effects of the pandemic. Foresight and an effective response to the pandemic is required, in order to ensure that the future implications of decisions made today do not cause further damage to the lives of the people who are often left excluded. Thorough evaluation of policies and their implementation, and the newfound enthusiasm and dedication to serve the people, could mean a transformation and a real attempt to address the inequalities and injustices that continue to haunt South Africa.

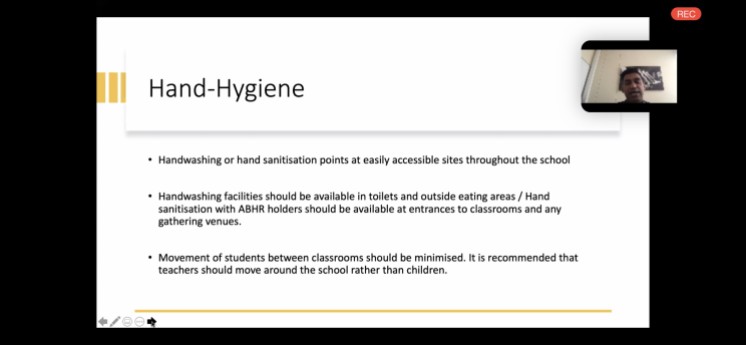

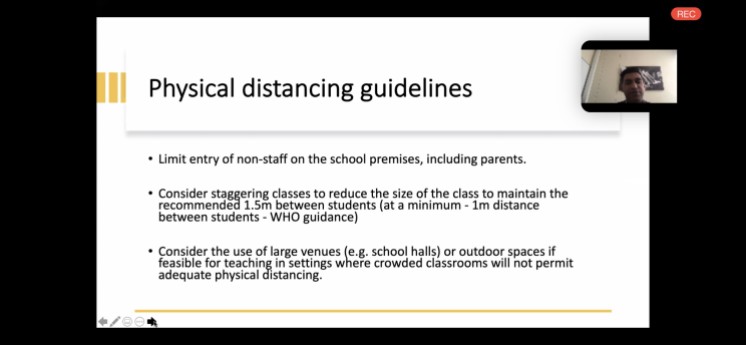

Self-quarantine /isolation/Social distancing

Most of the regulations that have been put in place have proved more effective and realistic in upper-middle-class societies due to their inadequate consideration of the realities of the poor and vulnerable people in our society. Although the government has made great efforts towards providing supplies such as food, dignity aids, and funds for the unemployed, these are by no means long-term or sustainable interventions. Some issues such as inadequate housing, and unemployment, go deeper and need long-term approaches that aim to address inequalities. Historical and present day structural vulnerability limits underprivileged people’s ability to “access basic needs such as food, medical care and proper housing”.[i] The legacy of the apartheid regime still exists as the most disadvantaged people live in low income and densely populated communities[ii] . This means that people are often unable to comfortably fit their entire family under one roof without sleeping toe to head. Communities that are structurally built to squeeze as many people as possible and provide foot-to-gate space in the name of a yard, make it difficult to keep one’s “social” distance.

These challenges have meant that most people living in poverty have not been able to adequately comply with these regulations. They are unachievable due to densely populated communities, and could further pose more danger in the event that a family member contracts the virus. The spread could be devastating for a whole family that is forced to squeeze into a small house/shack. It is important to acknowledge the more long-term and sustainable responses such as taps to provide running water for communities and other infrastructure that have been built during this time. This indicates that there is the possibility for more transformative interventions that will not only save the day, but provide security for generations to come.

Enforcement of Covid regulations

We have seen the “law” enforcement of these regulations in poor communities, taking a quick turn for the worst. “Legitimized” state violence and humiliation has put an added strain on vulnerable communities. Most people in townships, for example Evaton in Sebokeng, where official state offices are often a distance away, the time it takes to go stand in line for a permit and then go stand in line for groceries or healthcare poses a challenge. People often opt to go straight to their store or clinic, also hoping to not be outside long enough to meet the police or the army. Should one encounter the SAPS or SANDF on their way, they risk punishment and humiliation.

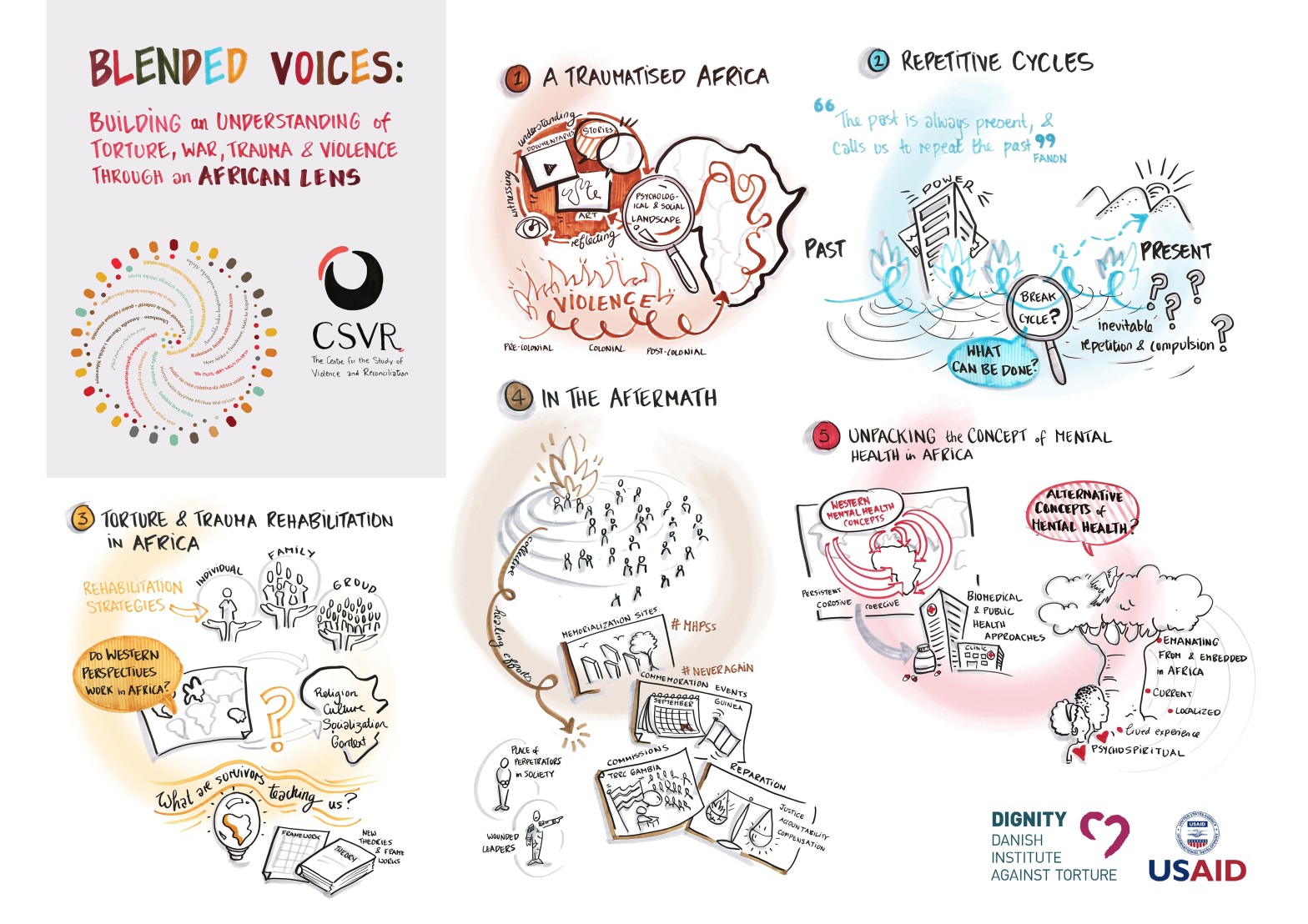

This form of intervention that has been adopted by some SAPS and SANDF personnel is reminiscent of apartheid state violence and the civil and political wars experienced by many of our clients, at the CSVR trauma clinic. The trauma from the past gets re-experienced in a process called traumatization.[iii] This should by no means be taken lightly, because oftentimes, unprocessed trauma makes its way down generational lines and results in what we see today in South Africa. A country ailing with trauma from the head down. I imagine there isn’t adequate context-sensitive and trauma-informed briefing and debriefing before, and during the deployment. Which would be a big oversight by the government. In fact, trauma-informed approaches should span to all areas of government due to our country carrying the burden of half cooked processes of rehabilitation. Therein lies the opportunity to begin to understand, empathise and intervene appropriately.

Dropping the ball.

I have found it particularly alarming that 424(as of the day I’m writing this), schools have been vandalized during the pandemic since schools closed. I wonder how this is possible with increased police and military presence, but an old lady selling atchar in Dobsonville is arrested because she does not have a permit? This is a classic example of letting all other balls fall and focusing only on one.

Furthermore, families are losing their livelihoods and corruption comes to steal from those most affected by the close of businesses, when they have no other way of making a living during lockdown. Unfortunately, the government has the responsibility to have its eyes and ears everywhere, at all times. Things like corruption, (where we see reports of mismanagement and theft of food parcels meant for communities, confiscated alcohol and other prohibited goods during lockdown being kept by the police, money being stolen from roadblocks) need to be rooted out, pandemic or not because they continue to undermine efforts of “moving the country forward”.

The spotlight on mental health

Mental health awareness has already been gaining momentum even before the country and the world, was hit by this pandemic. Since the start of the pandemic, greater levels of awareness on mental health have risen. I cannot open my internet browser without seeing an article on self-care, mindfulness or meditation. And I love it! In light of being forced to be alone or without the distraction of the outside (with the exception of the internet of course), more people are becoming aware of the self and getting to know and understand, hopefully, what goes on in our minds and hearts when we are not stuck in traffic or queues, or bars or school and work. I believe I speak for all when I say, it has not always been easy. For some, like myself, a very comfortable loner and introvert, the breaking point hit much later. For some, it has not hit as yet, and perhaps the lifting of the lockdown may bring emotions of anxiety as the comfort of being alone is taken away from us. So don’t worry, you’ll get your share! Jokes aside.

We should always spare a thought for those who are already dealing with mental health challenges from the past. Those in continuous traumatic situations. Those who have experienced past trauma and find themselves, in a way, “back at the scene of the crime”. Those faced with the power play of policing, being trapped in a house with your tormentor (as in the case of child abuse and neglect, and domestic violence), being triggered and re-traumatized by loss of personal space, uncertainty and seeing soldiers with guns, being overwhelmed by stress as you fail to put bread on the table for your family. Dare I say, we all, in one form or other, can find ourselves in this category.

I would like to draw attention to the realities of mental health, particularly in South Africa. It is still widely viewed as a privilege and something that only affluent people and those with resources can access. A number of reasons would support such sentiments. The under resourced mental health clinics and hospitals in rural areas and townships[iv] and the lack of mental health services in most schools, also in rural areas and townships, coupled with the stigma that surrounds mental health. All these undermine the efforts towards normalizing mental wellness and providing effective and quality mental health services. The point here is that, whilst some people have to make tough decisions with regards to starting online therapy or choosing between telephonic or video therapy with their current therapist, others have no idea that help exists. Many are not aware that their emotions are normal and valid, and that they can, with appropriate interventions, gain a better understanding of themselves, and perhaps, heal from their pain and trauma.

A lack of understanding and normalization of mental health, may lead to appropriate emotions in response to the pandemic such as anxiety, fear, helplessness and despair, being expressed inappropriately in the form of violence, neglect, self-harm. This may especially be the case where individuals or families have existing pathologies of transgenerational trauma or limited knowledge about emotional regulation, which is the case for many South Africans.

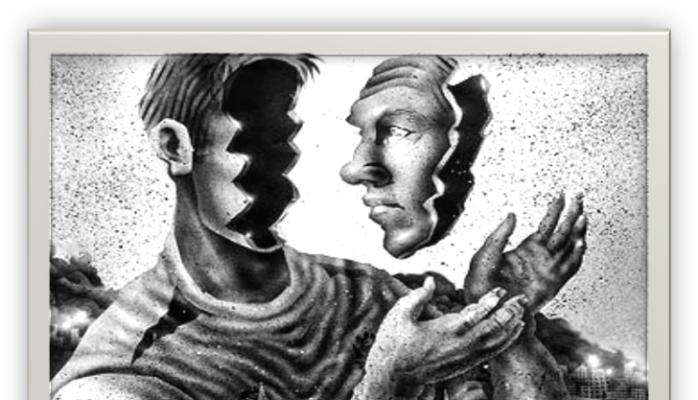

South Africa is a wounded country, led by wounded leaders[v]. This is a reality and we cannot continue tiptoeing around these issues because they threaten the dreams for healthy individuals and society, and a developed nation. What we need in these times, is empathy[vi]! Empathy provides the basis of human connections, which in return, informs human interactions. The lack of empathy means that human connections are based on a lack of compassion and understanding, and thus the interactions that follow are self-involved and lack the ability to see, acknowledge and feel with each other.

As we approach the lighter regulations of the lockdown, we should think more about what this period has taught us as a nation. We hope that the leaders will be able to reflect on their interventions and re-evaluate their approaches towards the betterment of people’s lives and the country as a whole. There are many texts that have been written during this period as many have shared their thoughts, experiences and considerations, to provide some light as to what the people are feeling and thinking.

South Africa cannot afford to take a hit on its road towards an equal and just society under the guise of swift interventions to flatten the curve. When handling or carrying out interventions and regulations in the South African context, it is not possible to roll out a blanket response. Due to the fact that South Africa is an unequal society and those on the wrong side of this inequality have found themselves fighting for their survival and dignity. Regulations should speak to the realities and context and have more foresight for the implications of such regulations and interventions, not only on the economy, but on the society’s physical and emotional wellbeing, post Covid-19.

Written by Charlotte Motsoari

[i] Quesada, J., Hart, L, Bourgois, P. (2012). Structural Vulnerability and Health: Latino Migrant Laborers in the United States. Medical Anthropology 30(4), 339-62. https://doi.org/10.1080/01459740.2011.576725.

[ii] Botes, T., CHOCHO, L.M.S., KELLOW, G., ENGELKING, E. B., KHOFI, L., BOSIRE, E., COSSA, ., MALOPE, D. (2020). How A Pandemic Shapes The City: Ethnographic Voices From South Africa. Medical Anthropology at UCL. https://medanthucl.com/2020/04/10/how-a-pandemic-shapes-the-city-ethnographic-voices-from-south-africa/

[iii] Retraumatization is a conscious or unconscious reminder of past trauma that results in a re-experiencing of the initial trauma event. It can be triggered by a situation, an attitude or expression, or by certain environments that replicate the dynamics (loss of power/control/safety) of the original trauma.

[iv] The South African Anxiety and Depression Group reports that there is only one psychiatrist for every 390,000 people in South Africa. Furthermore, two thirds of South Africa’s psychiatrists are employed in private practice.

[v] Mogapi. N. (2018). Cabinet Reshuffle: Wounded leaders, leading a wounded nation. Daily Maverick. https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/opinionista/2018-02-27-cabinet-reshuffle-wounded-leaders-leading-a-wounded-nation/

[vi] Empathy is the capacity to understand or feel what another person is experiencing from within their frame of reference, that is, the capacity to place oneself in another’s position.